Blog posts have half-lives of about 72 hours, and my most recent one is no exception. It got some good traction on Twitter, although I believe many people are as tired of debating the SAT as I am; it was picked up and posted in the Chronicle of Higher Education morning update (and to my surprise and their credit, no one here on the “Sixth Floor” asked me to remove the scatological term in the title). It got a lot more reaction on Facebook, where it was posted to a site I used to moderate but have since left. The messages from colleagues who were talking about the comments there caused me to go back and take a look. I’ll respond to those in a bit.

First, though, some history. These are my paternal great-grandparents Mary and Clemens, who came to America from what is now Germany (although it wasn’t then) in the mid-1840s. I never knew them, of course, but that scowl and lack of smile has been passed through the generations, it seems.

And this is my father, their grandson, and my mother on their wedding day in 1946.

They were born in 1916 and 1917, and if there was ever any hope of them going to high school, the Depression pretty much wiped that out, and, as I’ve written before, WW II probably wiped out some other dreams, too. There was something, though, about the neighborhood in which I grew up: Lots of WW II veterans who came back damaged, but who wanted much better for their children. How could you not after what you’d seen?

Anyway, even though all our parents smoked, and none had gone to college, none of us smoked and we all graduated. Traditions were changing. It was, as I’ve also written before, probably a remnant of the GI Bill that opened college to people who never had the dream of going, and the increase in attainment and the birth of America as the largest economic superpower are probably tightly related, although cause and effect are hard to separate (see below for more on my ability to distinguish).

But one thing seemed to be passed down in our family that is absent in other families: Don’t get above your raisin’ (in other words, remember where you came from). The one thing in our family that was either genetically embedded or conditioned into us was the sense that you don’t brag about what you can do, and you don’t feel superior to other people. ”He’s pretty full of himself,” was perhaps the worst thing you could say about someone in our house.

I still think “being full of yourself” is gross, for lack of a better word. But there does seem to be a peculiar subset of people who tout their ability to take a standardized test 20 or 30 or 40 years ago as a point of pride; and that thing–that narrow little skill–seems to be for them a defining characteristic. That skill also, frankly, seems to occasionally crowd out other life skills that one might aspire to.

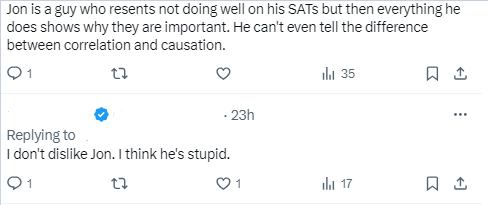

Consider this criticism from someone on Twitter:

For the record, The SAT doesn’t measure the ability to distinguish between correlation and causation. If you don’t know that, you shouldn’t be selling your advice about college to people.

I’ve scored in the 95th percentile or above on literally every standardized test I’ve ever taken, including the ACT (I never took the SAT, and growing up in Iowa, I don’t know if I’d ever even heard of it). I only say this because being a good scorer had apparently the opposite effect on me: It made me wonder why people who I thought were smarter than I was didn’t score as well. People who had a year more of math than I did scored lower on the math section of the test, and people who smoked me in chemistry scored lower on the science section: How could that happen? Even though I admit there were times I was proud of the score, and even pulled it out a few times in arguments when the beers were flowing, it never really seemed to be substantive to me.

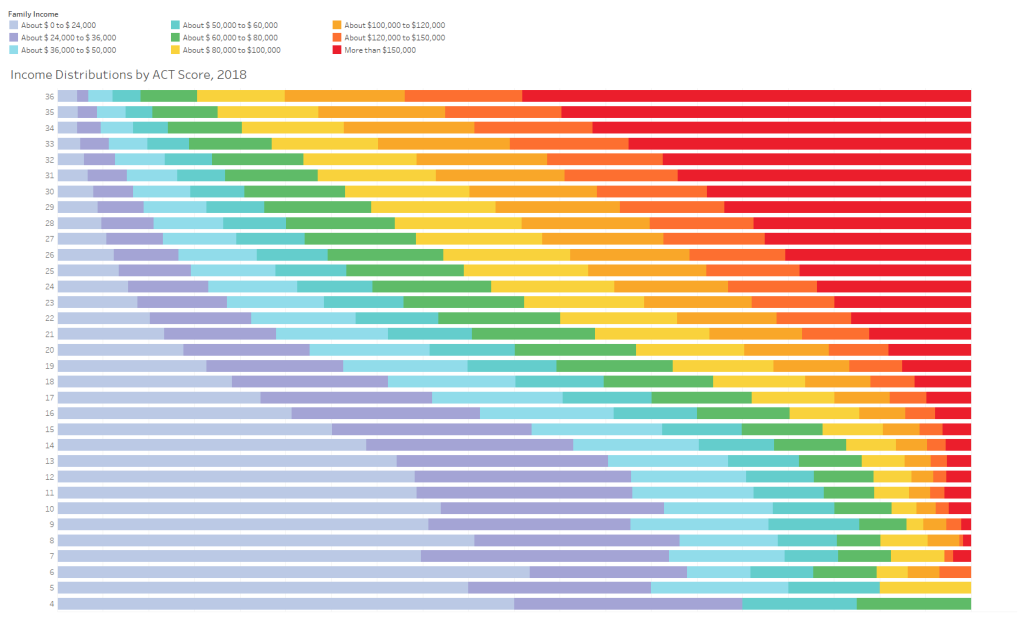

The comment about correlation and causation is almost certainly in reference to this chart I’ve posted several times, using data I extracted from the ACT software colleges used. Although it’s from 2018, this pattern held true over time; it’s not unique to this year. You can see that at every ACT Composite score, the probability of hitting that score increases with income. And it’s such a perfect stepwise progression, you’d have to think it was designed that way.

I know, of course, that being wealthier doesn’t cause you to score higher (although the “rich people are smarter” response frequently appears from blue-check crypto guys on Twitter.) But it’s clear that the wealthy–who generally prize a ticket to the Ivy League the way they prize Patek Phillippe watches and Hermes scarves–do things to ensure those scores are higher. In addition to expensive tutoring, they also send their children to schools where the SAT is a part of the curricular focus, as evidenced by the high test scores at these schools. If you see a dog chasing its own tail at this point, join the club.

And, for those who can’t seem to connect the dots as well as they can fill in bubbles, here’s why that chart is important: If you select applicants mainly or only from those students who score in the top three or four or six rows of that chart, you’re going to discover that you’re merely perpetuating privilege, notwithstanding the few diamonds in the rough everyone likes to fawn over. Maybe that’s your goal, but if it’s not you should at least be aware of what you’re really doing when you claim to be selecting “the best.”

(See also in this blogpost who is advantaged and disadvantaged by the SAT, using the College Board’s own research.)

So onto the Facebook response, which was driven by two ardent supporters of tests. (And thanks to Jon Burdick who actually worked in Ivy League admission for coming to my defense in my absence.) One of them took exception to my suggestion in the previous post that College Board might have planted this story with David Leonhardt, who just so happened to be at Yale at the same time as David Coleman. I pointed to the fact that this seemed like it was delivered as a neat little package, with the ends tied up so nicely, and a dearth of research to present other opinions, that suggested to me it was possible. Of course, I don’t know this for a fact. (It is quite interesting that the Times has changed the title of the headline, however.)

But that observation got me called a conspiracy theorist. In the last post, I linked to this, where Richard Atkinson, then the president of the UC system, pointed out that College Board did exactly that. It’s just three minutes long, and worth a view.

Second, recall that College Board took out a full-page ad in the Atlantic and disguised it as an editorial piece.

Third, in about 2015, I was contacted by someone who has been tight with the College Board as he was editing a book, claiming they wanted to do a fair and balanced discussion of tests and test-optional. I declined, because I smelled a rat, and the book “Measuring Success” was in fact a promotional piece touting testing; the editors even thanked the College Board Communications Team in the foreword for all their hard work pulling it together. Interestingly, as Paul Tough pointed out, the tables of research in the book, and the research itself that cited the “grade inflation” trope were actually wrong, and showed the opposite of what they had claimed.

The College Board for years cited the folly of test-prep services. Before they got into the business of test-prep services. It seems that $omething changed their mind.

And finally, the now-legendary puff piece on David Coleman and the re-design of the SAT was–as confirmed by former College Board employees–offered as an exclusive to the NY Times in exchange for favorable coverage. The College Board knows what side its bread is buttered on. Don’t ever think they don’t.

So, maybe I’m a conspiracy theorist. But I don’t think so.

That same person suggested the Dean of Admission at an Ivy League institution had said that the SAT was a better predictor of college grades than high school GPA. That’s funny, because this is what that same person said not too long ago.

That’s an argument even I make. But that incremental predictive power is really tiny, in most studies not conducted by the College Board or people who are affiliated with the College Board. (Is the juice worth the squeeze?)

Here is what else he said in that same article, by the way, reflecting on review without tests after a professional lifetime of using them.

Finally, in that last blogpost, I said I wasn’t going to cite statistics because statistics don’t change minds. To which one person, connected (the last time I looked) to the National Test Prep Association, cited statistics and took me to task.

Here’s the thing: Many of the things claimed in the Leonhardt article are not even claims the testing agency makes. If you want to look at research by someone who has studied the SAT and its predictive power the longest, just click here and read those pieces. Argue with him. (He also wrote a rebuttal of the California Faculty Senate study that cited the College Board research over 50 times, suggesting they had made amateurish mistakes. Leonhardt cited the former, but didn’t mention the latter.)

Of course, in my previous article, I cited this thread which contained statistics, and which tore apart the analysis in the Leonhardt article, and now Jesse Rothstein, also at Berkeley, has sent this letter to the Times:

And yet, citing this research has not changed his mind. To which I reply, QED. Told ya so. Statistics don’t change the minds of people who think choosing one answer from the options presented makes you smart. I could do that easily.

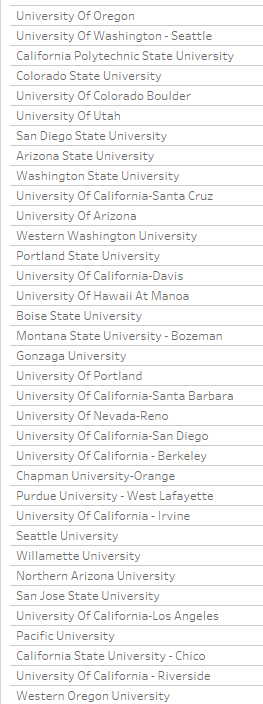

Use the SAT if you want, and don’t if you don’t find it valuable. Of the top 35 overlaps schools in our 2023 class, only one requires the SAT, and that one comes in at #25. Most are pemanently test-optional or test-free. No public west of the Mississippi requires the SAT or ACT. So, I don’t care.

I do care when people get their facts wrong and try to convince me they’re right. And I’ll always push back on that.

Great piece! And so disappointed in David Leonhardt – who I used to read religiously! Wouldn’t it be great if journalist spoke to the counselors who work with first-generation students from low resourced high schools and communities. We don’t need statistics to tell us what we have seen and learned over the past 5 years!

LikeLike