Microcredentialing programs remain nascent at many institutions, but interest continues to grow. As the demand for flexible learning experiences increases, stakeholders might find renewed interest in and uses for microcredentials.

EDUCAUSE is helping institutional leaders, technology professionals, and other staff address their pressing challenges by sharing existing data and gathering new data from the higher education community. This report is based on an EDUCAUSE QuickPoll. QuickPolls enable us to rapidly gather, analyze, and share input from our community about specific emerging topics.Footnote1

For this QuickPoll on microcredentials, we partnered with WCET (WICHE Cooperative for Educational Technologies), a trusted leader in digital learning in higher education.

The Challenge

In the 2023 EDUCAUSE Horizon Report: Teaching and Learning Edition,Footnote2 we described how microcredentials programs are gaining momentum and maturity. EDUCAUSE has defined microcredentials as "obtaining nondegree certification or competency in a specific area of skill or knowledge, often in smaller and shorter segments than the typical college degree." Learners are looking for flexible ways to achieve their educational goals, and a growing number of families and students are questioning the value of a college degree. Microcredentials seem to be an attractive option for meeting students' needs, but higher education professionals still do not have widely agreed upon resources for defining, designing, delivering, supporting, or evaluating microcredential programs. In this QuickPoll, we asked educational technology professionals about the current state of microcredentials at their institutions.

The Bottom Line

Our data suggest that microcredential programs are in fairly early stages; only 9% of QuickPoll respondents indicated that their institution has a mature microcredential program (i.e., well-developed and several years old). Institutional leaders do see value in microcredentials—specifically, they provide flexible, affordable learning opportunities for students, faculty, staff, and even the community. Institutions with a cohesive strategy, strong leadership, and clear policies are growing successful microcredential programs. However, challenges such as institutional silos and lack of funding can be roadblocks to advancement. Microcredentials may be on a slow and steady rise to the mainstream, or mounting obstacles could end that progress.

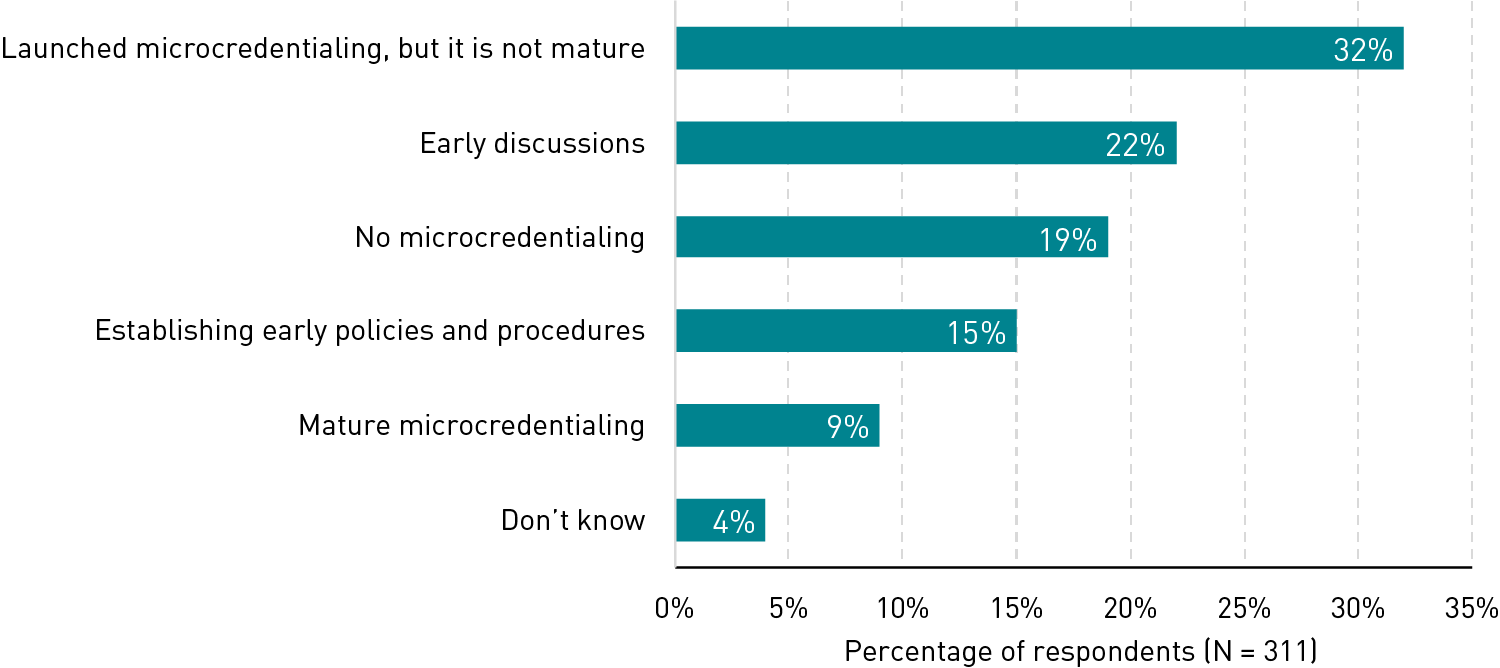

The Data: Microcredential Program Maturity

It's a work in progress. Though higher education stakeholders have been interested in microcredentials for at least a decade, many programs are still just getting off the ground. When asked about the maturity of microcredentialing at their institution, only 9% of respondents said that they have mature microcredential programs (i.e., well-developed and several years old; see figure 1). Nearly one in four respondents said that they do not have any microcredentialing at all or don't know about any microcredentialing at their institution (19% and 4%, respectively).Footnote3 The majority of respondents (69%) indicated that they are in early discussions, are establishing early policies and procedures, or have launched microcredentialing that is not yet mature (22%, 15%, and 32%, respectively).Footnote4

Respondents who said that they already have at least some microcredentialing at their institutions were asked about the scale of those programs. A slim majority of those respondents (55%) said that microcredentialing is available in multiple programs or departments but is not yet an institution-wide offering. About a third (31%) of respondents said that microcredentialing is available in only one or two programs or departments, and just 14% said that microcredentialing is offered institution-wide across most or all programs and departments. More-mature microcredentialing programs are more likely to operate at a larger scale—nearly half (46%) of respondents who said that they have mature programs also said that microcredentials are offered institution-wide, as compared to just 5% of respondents who said that they have a microcredentialing program that is not mature.

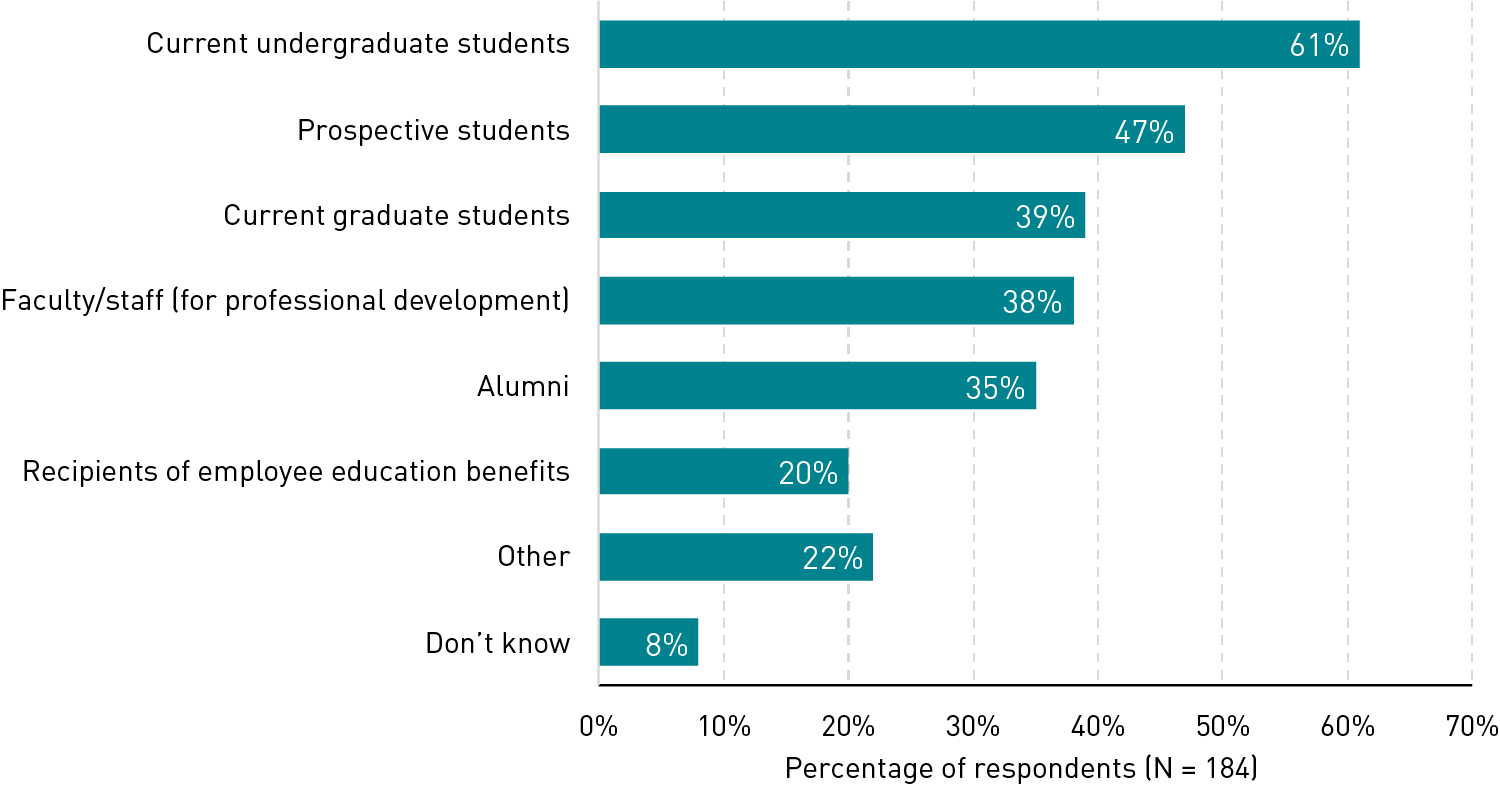

There's something for everyone. Though the overall maturity of microcredential programs might be limited, existing offerings have evolved to serve a variety of audiences and subjects. From a list, respondents selected all of the individuals who could earn microcredentials at their institution. Together, the intended audience for microcredentials comprises a wide range of individuals (see figure 2), from current undergraduate and graduate students (61% and 39%, respectively) to prospective students (47%), faculty and staff (38%), alumni (35%), and recipients of employee education benefits (20%). More than one in five respondents (22%) selected other types of individuals; open-ended respondents described audiences such as lifelong learners, professionals seeking continuing education, and volunteers.

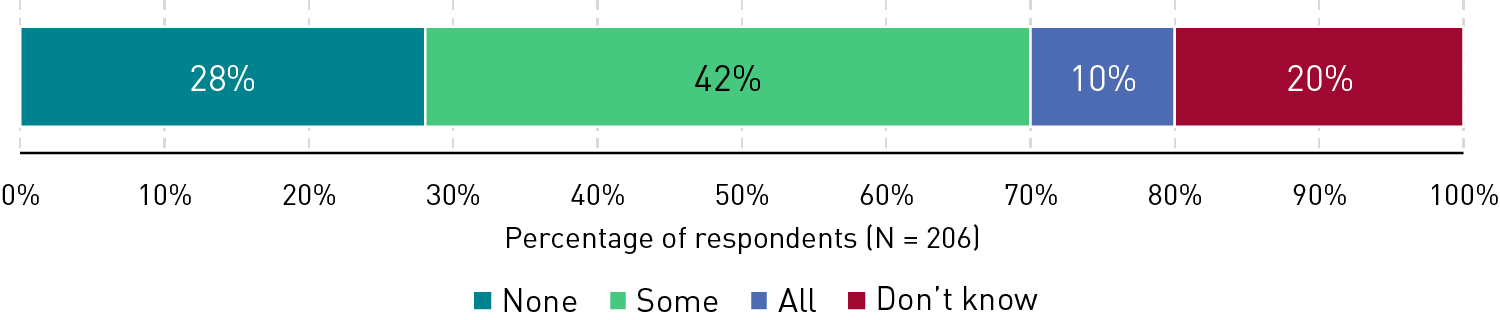

Given this variety in intended audiences, it is no surprise that just 10% of respondents reported that all of their institution's microcredentials are attached to credit-bearing offerings (see figure 3). Over a quarter of respondents (28%) said that none of their microcredentials are attached to credit-bearing offerings, and a plurality of respondents (42%) said that only some of their microcredentials are attached to credit-bearing offerings. Further, just 6% of respondents said that all of their microcredentials are stackable toward a higher credential, with a plurality of respondents reporting that only some of their microcredentials are stackable (46%). A quarter of respondents (25%) indicated that none of their microcredentials are stackable. Taken together, these data suggest that microcredentials, historically referred to as "alternative credentials," are not widely integrated into formal degree programs but are instead offered as a supplement or even an alternative to formal programs.

In open-ended comments, respondents also provided a long list of programs and content areas that are the primary focus for microcredentialing at their institution: traditional degree programs such as accounting, business, information science, marketing, and engineering; professional and personal skills such as technical writing, world languages, laboratory safety, equity and inclusion, and public speaking; and emerging topics such as cannabis chemistry, virtual reality, and digital transformation.

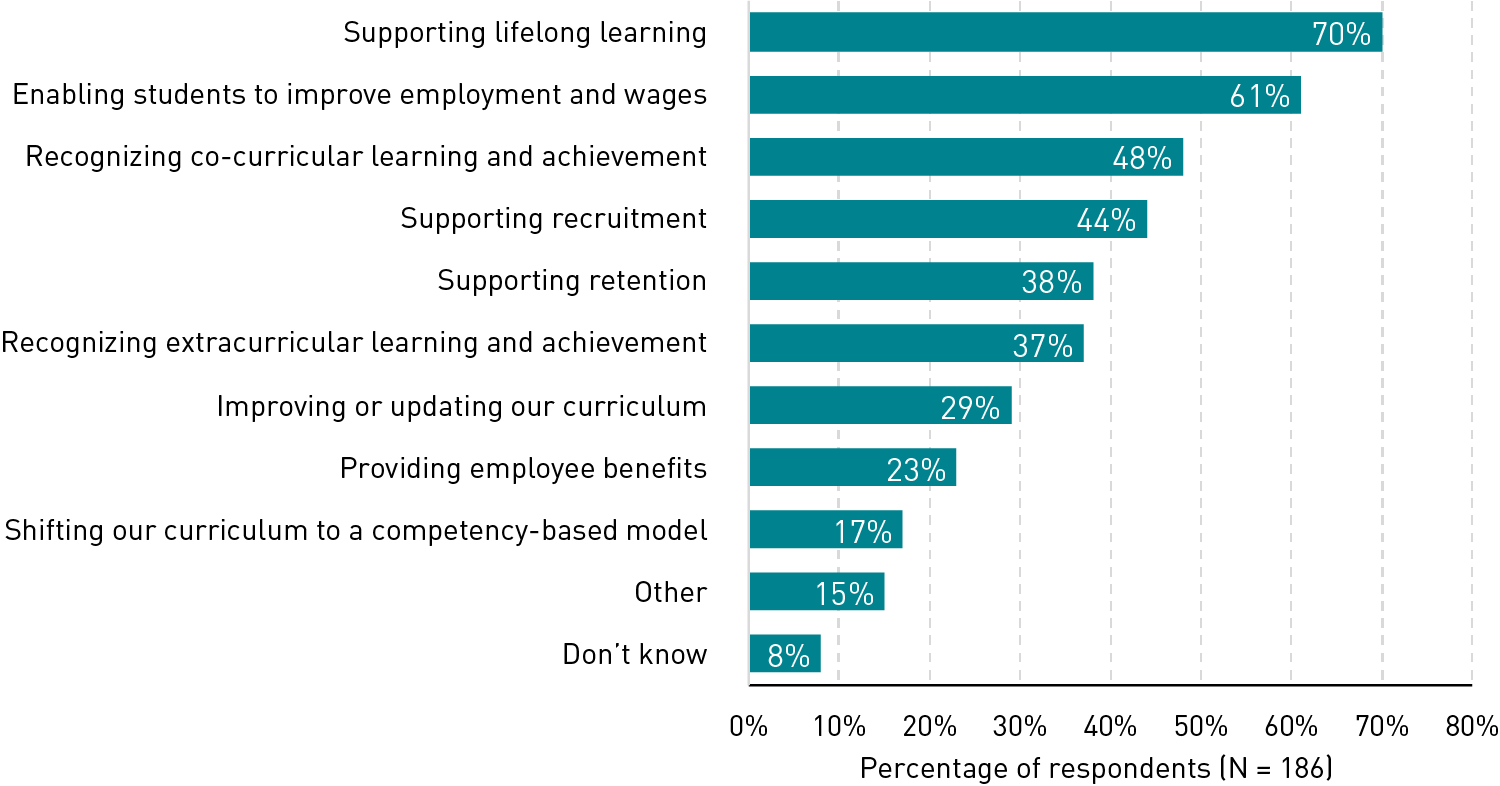

The Data: Designing Microcredential Programs

Microcredentials serve many purposes. In keeping with the findings described above, respondents indicated that the primary goals of microcredentialing are not necessarily related to formal degree programs (see figure 4). From a list, respondents selected all of the goals of microcredentialing at their institution. The three most-selected goals are supporting lifelong learning (70%), enabling students to improve employment and wages (61%), and recognizing co-curricular achievement (48%). Further, about two in five respondents chose supporting recruitment or retention (44% and 38%, respectively) as goals of microcredentialing. These data suggest that institutional stakeholders are leveraging microcredentials as added value to traditional degree offerings in efforts to recruit and retain students. One respondent mentioned that a primary institutional goal of microcredentials is to "increase the perception of value in our general education curriculum."

Respondents who indicated that they have other institutional goals for microcredentialing provided further insight in open-ended responses:

- Chunking degrees into small pieces

- Connecting learning to workforce skills

- Providing the institution with a new revenue stream

- Supporting learner motivation and engagement

- Providing shorter and more affordable learning opportunities

Institutions are working with industry. Given that work and career-related goals are one of the central priorities of microcredentialing programs, collaborations between institutions and industry partners could be valuable in the design of such programs. Indeed, more than half of respondents indicated that some or all of their microcredential criteria (47% and 9%, respectively) are developed with external industry partners. Just over one in five respondents (21%) said that all of their microcredential criteria are developed internally. Notably, the majority of respondents who said that all or some of their microcredential criteria are developed internally also reported that some or all of those criteria are informed by external industry standards (65% and 15%, respectively). Only 10% of respondents said that none of those criteria are informed by external standards.

The Data: Supporting Microcredential Programs

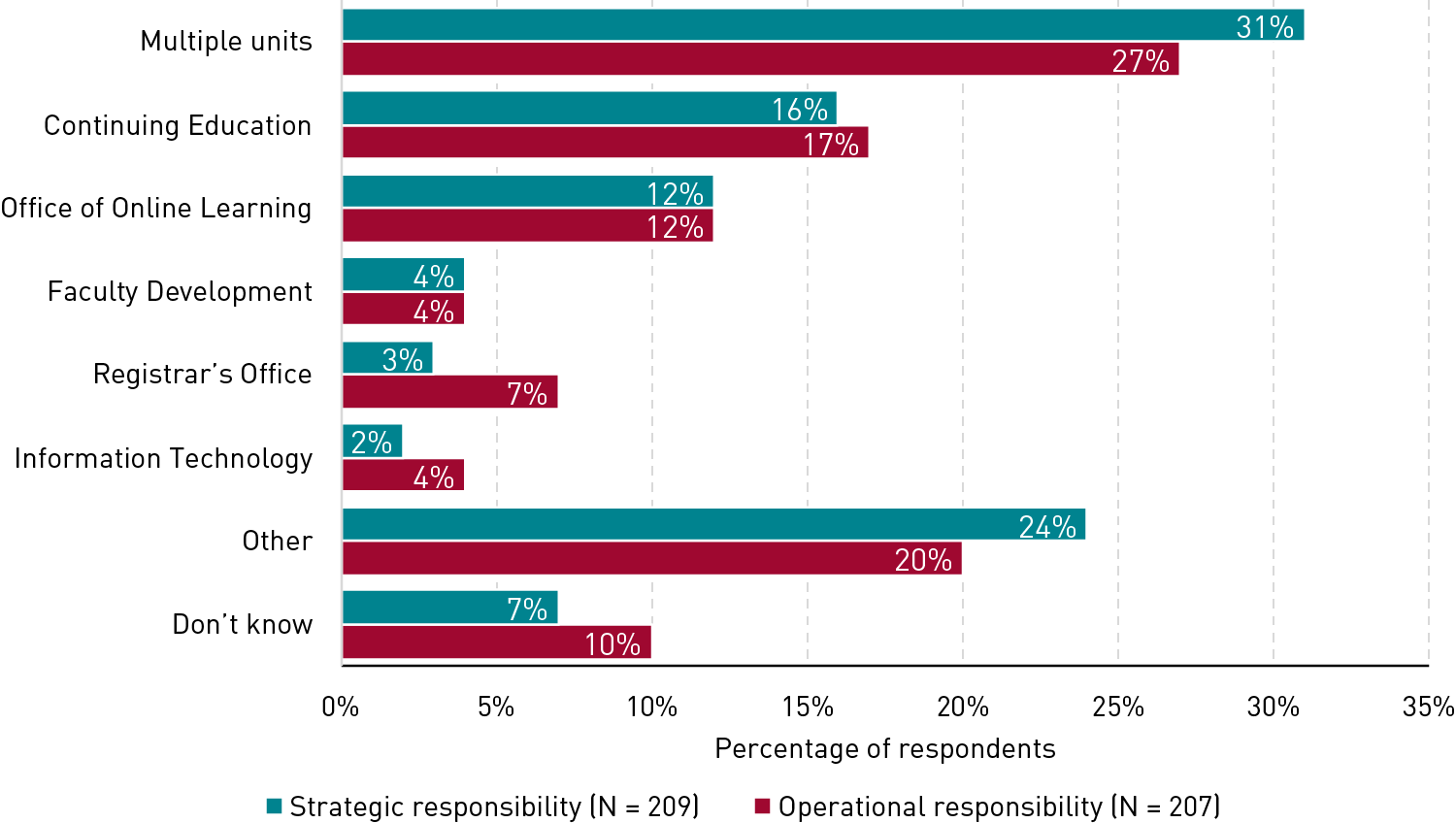

Microcredentialing is a team sport. No clear consensus emerges on a singular unit that should be responsible for microcredentials at institutions. Nearly a third of respondents (31%) indicated that multiple units have strategic responsibility for microcredentials at their institution (see figure 5), and over a quarter (27%) said that multiple units have operational responsibility for microcredentials. Respondents also selected continuing education, the office of online learning, faculty development, the registrar's office, and IT as units responsible for microcredentials. Nearly a quarter of respondents said that other units not included in our list have strategic or operational responsibility (24% and 20%, respectively) for microcredentialing at their institution. Open-ended responses included academic affairs; the provost's office; the college of undergraduate studies; a dedicated department, committee, or cross-functional team; and deans or department chairs.

Common Challenges

What is a microcredential? Perhaps the most pervasive and basic challenge for institutions exploring microcredential programs is a lack of agreement among stakeholders about what microcredentials are and what value they might bring.Footnote5

"It is confusing. Academic microcredentials, nonacademic microcredentials. There are still many moving parts."

"Competing visions for microcredentials. Faculty misunderstandings about what microcredentials are and their potential value for learners and the university."

"Taxonomy and terminology. Also what taxonomy of skills do we align it to?"

Without a shared understanding of and vision for microcredentials, stakeholders are not able to create cohesive goals or policies. Respondents reported that they lack agreement in policy and strategy and have no clear leadership or governance to unify relevant institutional units.

You can't know what you don't measure. Many questions about the efficacy and tangible value of microcredentials have persisted, particularly as institutional leaders make difficult decisions about investing limited resources. Fewer than one in ten respondents (9%) reported that they track employment placement for microcredential earners. As one respondent described:

"[We have encountered challenges] determining whether these are really valuable to students or employers; determining whether there is value in having 'extracurricular' badges for soft skills. Does an employer really believe that a student has a communication badge? How do we determine ROI?"

Promising Practices

Align strategy, process, and support. Clear goals and strong leadership are essential elements for any institutional program, including microcredentials. In open-ended responses about particularly effective practices, respondents pointed to cohesive leadership, concrete policy, and alignment of curricula to desired outcomes. As one respondent explained:

"Ensuring demonstrable knowledge, skills, or competencies gained through learning has been a very effective practice. We are aiming for real and measurable learning, not just participation badges."

Of course, microcredential programs require funding to get started and stay running. Respondents described a variety of funding sources for their programs:

- Grants and pilot research funds (e.g., internal, government)

- Strategic investment funds

- LMS procurement funds

- Individual unit or program budgets (e.g., provost, academic departments)

- Tuition revenue

- Cost recovery (i.e., revenue from microcredential program)

Find the right partners. As previously mentioned, more than half of respondents indicated that some or all of their microcredential criteria (47% and 9%, respectively) are developed with external industry partners. Respondents described the value in working with external partners:

"[We are] partnering with external organizations to co-design and co-value microcredentials, making the value proposition for all three stakeholder groups—learners, employers, and university. Treating the value of microcredentials to be less as 'credentials' and more as 'connectors.'"

"When a certificate series of badges was built with input and financial support from a major employer, we found that there was a good, steady stream of students completing not only the badges but the whole certificate."

Learn from peers. Finally, there's no need to reinvent the wheel. Connect with colleagues to learn and collaborate:

- EDUCAUSE Connect Microcredentials and Badges Community Group

- EDUCAUSE Learning Lab: "Microcredentialing: Aligning Learning to Employer Needs and Implementing a Comprehensive Learner Record"

- EDUCAUSE Webinar: "A Student-Centric Framework for Measuring the Value of Credentials"

- EDUCAUSE Library: Badges and Credentialing

All QuickPoll results can be found on the EDUCAUSE QuickPolls web page. For more information and analysis about higher education IT research and data, please visit the EDUCAUSE Review EDUCAUSE Research Notes topic channel, as well as the EDUCAUSE Research web page.

Notes

- QuickPolls are less formal than EDUCAUSE survey research. They gather data in a single day instead of over several weeks and allow timely reporting of current issues. This poll was conducted between May 16 and May 17, 2023, consisted of 20 questions, and resulted in 311 responses. The poll was distributed by EDUCAUSE staff to WICHE members via email and social media and EDUCAUSE members via relevant EDUCAUSE Community Groups. We are not able to associate responses with specific institutions. Our sample represents a range of institution types and FTE sizes. Jump back to footnote 1 in the text.

- Kathe Pelletier, Jenay Robert, Nicole Muscanell, Mark McCormack, Jamie Reeves, Nichole Arbino, and Susan Grajek, with Tracey Birdwell, Danny Liu, Jean Mandernach, Ayla Moore, Anna Porcaro, Rayan Rutledge, and Johann Zimmern, 2023 EDUCAUSE Horizon Report, Teaching and Learning Edition (Boulder, CO: EDUCAUSE, 2023). Jump back to footnote 2 in the text.

- Respondents who indicated that they do not have microcredentialing at their institutions were not asked any other survey questions. Jump back to footnote 3 in the text.

- Due to rounding errors, proportions of answers to some questions may add to more than 100%. Jump back to footnote 4 in the text.

- Open-ended comments have been lightly edited for readability. Jump back to footnote 5 in the text.

Jenay Robert is Researcher at EDUCAUSE.

© 2023 Jenay Robert. The text of this work is licensed under a Creative Commons BY-NC-ND 4.0 International License.