When Tweets Go Wrong: Dealing with Negative Reactions on Twitter

Have you worried about a tweet going wrong?

A common fear or anxiety academics have about Twitter is that someone will have have a strong negative reaction to something you share.

The extreme version of that fear is: What happens if your tweet becomes front page news?

Today I’m talking about what happens when tweets go wrong.

- What negative reactions look like on Twitter

- To engage or not: thinking about responding

- When tweets do make the headlines for negative reasons

- And, how it’s not that bad (what I’ve learned)

On Twitter, anything that has high engagement has the possibility of going viral. You don’t need a big audience on social media to reach thousands of people, especially on Twitter. Tweets from accounts under 200 followers have gone viral nationally. And accounts with small followings go viral among academics all the time.

Get the right combination of people who care early on + people who can relate when seeing your tweet for the 1st time, and any post has the potential to go viral.

Tweets that go viral might end up in the news. That can be great, if you’re sharing a resource or starting a conversation. Viral tweets sometimes happen when people are celebrating good news with you. Professors have gone viral for being compassionate. Graduate students can go viral talking about their research interests.

Going viral can be unnerving. When you realize your words are being seen by thousands in real-time, that people are reacting as you post…If you’re writing a thread, your tweet may go viral before you’re done with your last tweet.

“By the end of the day it was clearly something far beyond anything I’d ever done online and you know, approaching over a million kind of viral interactions.” Read my interview with Dr. Walter D. Greason and learn about his viral tweet that was translated into 7 languages.

Tweets that end up reaching a lot of people can go wrong as well. And that’s what I’m diving into today.

I don’t want to scare you. Most negative reactions aren’t that bad. Some, like unfollow and mute are passive, and more about what that person wants to see daily.

So, lets talk about tweets gone wrong, and what to do about it.

Subscribe to The Social Academic blog.

The form above subscribes you to new posts published on The Social Academic blog.

Want emails from Jennifer about building your online presence? Subscribe to her email list.

Looking for the podcast? Subscribe on Spotify.

Prefer to watch videos? Subscribe on YouTube.

Negative reactions on Twitter

When I first joined Twitter, I was scared I was going to say the wrong thing. I was a graduate student. And, I was on the professional writing team for my academic department. So I felt a responsibility to represent my school even if it wasn’t formalized.

That was one fear I experienced when it came to social media. Moving past my fear of saying the wrong thing took time. And, experiencing a negative reaction personally.

You see, no one uses the hashtag #PoetryTwitter. The 5th complaint about a lack of poetry community on Twitter that month appeared on my feed. It was from a well-published poet who had quite a community themselves. But I wasn’t surprised, because it’s a complaint I see often: ‘All the poetry hashtags are filled with bad poetry, where’s the conversation?’

I had just finished a bunch of social media training and was like: I have the solution. I’ve solved the problem about lack of poetry community on Twitter. They just need a hashtag! One that’s for events, readings, announcements, and community.

#PoetryTwitter would have solved all those problems. At the time, it was completely inactive, like 1-2 posts/month. But when I tweeted about it, people did not want a solution.

I had tagged a few people I’d seen talking about this before, and let’s just say one did not want their day interrupted.

It didn’t even matter that some people who saw my tweet thought the hashtag was a good idea. I got a negative backlash from someone I respected, and had read quite a bit of, and that was it for me. I deleted the tweet, and haven’t spoken much with poets about social media since.

Did I take that negative reaction personally? Yes.

It was a negative reaction to something I thought quite a bit about. I was trying to help a larger group of people. And, I tagged only people who I knew were interested in this particular topic. I was disappointed.

But when I think back about why I deleted the tweet, it was because I didn’t want to keep being disappointed.

A negative reaction to something you share can have long-term effects. It did for me.

Learn how to start managing your online presence for free.

Here are some of the negative reactions you might experience on Twitter. The most common we think of are

- Unfollow

- Mute

- Block

- Report

Some people choose to respond more directly, and their negative reaction might look like a

- Retweet with a quote

- Reply in a negative way

Some negative reactions involve sharing your tweet with a larger or external audience

- Share via DM

- Screenshot (+ share)

- Reporting to employer

I’m writing these tips in case you have to use them one day. I hope you don’t have to deal with trolls or harassment on social media, but bookmark this page just in case.

Subscribe to The Social Academic blog.

The form above subscribes you to new posts published on The Social Academic blog.

Want emails from Jennifer about building your online presence? Subscribe to her email list.

Looking for the podcast? Subscribe on Spotify.

Prefer to watch videos? Subscribe on YouTube.

Unfollow, Mute, Block, and Report

The most common reaction to something you share is one you may not notice. If someone doesn’t like your post a lot, they’ll unfollow you.

When someone unfollows you, it doesn’t necessarily mean they don’t like you. It means they don’t want to see the content you share in their home feed.

I like celebrities I don’t follow because I just don’t care about their social media posts. They don’t share content I’m interested in seeing. So while we can think of an unfollow as a negative reaction, don’t take it personally.

Another option people take is the mute feature. It allows you to remain following someone, but not have to see them in your feed.

The nice thing about the mute feature is that you can use it for accounts you don’t follow. Let’s say there is someone in your field who is just prolific on social media. Their tweets are appearing on your feed all the time even though you don’t follow them. Well, you might choose to mute their tweets, so they’re not appearing all the time.

Learn how to use mute on Twitter.

If you’re dealing with someone harassing you, the mute feature is a good option. But you may also choose to block them. Blocking someone on Twitter will prevent them from seeing or interacting with your tweets. When you block an account, they will be able to tell they’ve been blocked. So sometimes, using mute can be better.

Learn how to block someone on Twitter.

I had to block someone I went to grad school with because they attacked their personal audience on social media. I had a negative reaction to what they shared. When I called them out on it, they would not stop messaging me. Sure, mute might have been the politer option, but they were so rude over direct messages, why bother? There isn’t a right choice for everyone, and that’s why I’m giving you all the options.

Dr. Monica Cox (@DrMonicaCox) has used blocking and reporting when dealing with negative reactions. I asker her what the decision making process was like. Dr. Cox said, “It’s easy. When I hear noise, I either report or block them. The noise is negativity that isn’t constructive. The person is usually persistent, and they are seeking attention. If it happens more than twice, I block them because they are consuming energy I don’t want to put into a social media interaction.”

This is great advice. Thinking about how much time and energy negative reactions are taking up may help you make a decision.

If someone unfollows, mutes, or blocks you, that’s their choice. It means they no longer want to interact with you on social media, and you shouldn’t force them.

Unfollow, mute, and block are somewhat passive ways to have a negative reaction. Though occasionally, block can result in a public conversation about the fact blocking occurred and why.

Sometimes, you need to respond more actively, like when you see hate speech, threats, or violence on social media, you can report the tweet for review. If the post breaks the Terms of Service for the social media platform, it will be removed. And, under certain circumstances, the account might be suspended.

Report is a feature you should use when needed. And if something is very concerning, let your friends know. Typically more reports result in a faster review.

Learn how to report a tweet, list, or direct message on Twitter.

Back to the list of negative reactions

Negative replies or retweets with a quote

The type of negative reaction most people experience at some point or another responses that disagree with what you say. These often look like

- Retweet with a quote

- Reply in a negative way

These responses are generally because someone reading your tweet

- disagrees with what you said

- is correcting a mistake

- is confused about something

- has misread or misunderstood what you said

- has a question that comes across rude (but is oftentimes genuine)

- is a troll

There are many reasons for someone to have a negative reaction. Understanding their reason will help you respond. We’ll talk more about responding to these types of reactions in a sec.

People disagree with me on Twitter sometimes, like when I say something about how great I think LinkedIn is.

Sometimes they reply to the tweet. I like this because I can have a conversation with them about why they feel that way. I can learn what their experience has been.

Occasionally, people will share my tweet using retweet. And they’ll add a quote. Retweeting with a quote is a more public way to leave commentary (i.e. “I’ve never found LinkedIn helpful, have you?”).

A retweet with a quote suggests you might want to start your own conversation about that topic. Or, it’s something you care strongly about want want the people who follow you to see.

Being trolled usually involved 1+ people using reply and retweet with a quote a lot. You might be trolled by someone you know who is particularly upset.

Dr. Monica Cox recently dealt with a harasser on Twitter, saying she noticed “something about their voice that is off and odd. Instead of chiming in, even if they disagree, they are negative.”

You can spot trolls often because they’re “anonymous and have few followers.” Dr. Cox says, “When a person pokes and doesn’t want to be found, it is a sign that they aren’t engaging for good reasons.”

Dr. Cox felt “confused at first and then upset because the attacks were harmful and personal.” She said the anonymity of it made it worse because “it didn’t feel like a fair exchange.”

The fear most people have about trolls is that they’re more organized. That when 1 troll alerts their group, all the sudden it rolls into worse negative reactions, like report, and sharing your tweet with say, your employer.

Learn more about how Twitter handles SPAM and fake accounts.

Back to the list of negative reactions

When someone shares your tweet in a negative way

The type of negative reaction that causes the most concern for academics is that someone might share your tweet in a negative way. For instance, they’ll share it with your colleagues, or report you to your employer.

Worst-case-scenario, your tweet ends up in the headlines in the national news. It’s happening more than ever.

Everything you post on social media can be shared. And that’s true even if you have a private account, and you only connect with people you know.

So let’s talk about negative reactions that involve sharing beyond Twitter

- Share via DM

- Screenshot (+ share)

- Reporting to employer

Tweets can be shared quite easily via direct messaging. Sharing a tweet via DM is a private way to let people know about something. A link to a social media post can also be shared via email, text, etc. Unless you have a private account, anyone can see your tweet.

Subtweet is a term people use to describe tweets that are complaining about someone but don’t tag that person. When you tag someone, you let them know about it and essentially give them opportunity to respond.

So even if you don’t tag someone, if people can figure out who you’re talking about you may get negative reactions. Sometimes, you won’t know those reactions are going on.

Here’s an example. Professors complain about their students on social media. Sometimes it’s blanket statements like “class was so frustrating today” or “no one did the reading.” Other times, it’s more direct.

Let’s say you’re a graduate student and your professor says something bad about your friend on Twitter. Even though they don’t mention your friend’s name, you know it’s about them because you were in that class. Will you pretend you never saw the tweet where your professor complained about them?

There isn’t a right answer to the question, but when I’ve asked grad students this before they say something like “I’d want to give my friend a heads up.”

Sharing the original tweet via direct messaging, email, or text is one way to do that. All you need is the link.

Another is to screenshot the tweet and share the photo.

Don’t rely on deleting your post to save your tweet from being shared. Screenshotting is an easy way to capture content immediately. If people see something really shocking they think you might delete, they’re more likely to screenshot it just in case.

Media outlets do not need your permission to share your social media posts, though some may ask. Tweets can be embedded directly on websites and in news articles.

And, screenshots or a link to your tweet might be shared with your employer if someone is particularly upset with what you’ve shared. I once reported a professor for saying their grad student should be killed for a grammar mistake. And I’d do it again.

When tweets get reported to your employer, it’s likely because you’ve had not just 1, but a bunch of negative reactions.

You may even be dealing with trolls, those often anonymous social media accounts that reply, report, and retweet with the intent to further harass.

The people who report tweets to employers often feel very strongly about their reason for doing so. It might be a student, a parent, a colleague, or someone who has no idea who you are.

You have to be aware of these possibilities before you tweet.

Subscribe to The Social Academic blog.

The form above subscribes you to new posts published on The Social Academic blog.

Want emails from Jennifer about building your online presence? Subscribe to her email list.

Looking for the podcast? Subscribe on Spotify.

Prefer to watch videos? Subscribe on YouTube.

Back to the list of negative reactions

To engage or not, when to respond on social media

So, when do you engage with negative reactions? When do you ignore them? The answer is different for everyone.

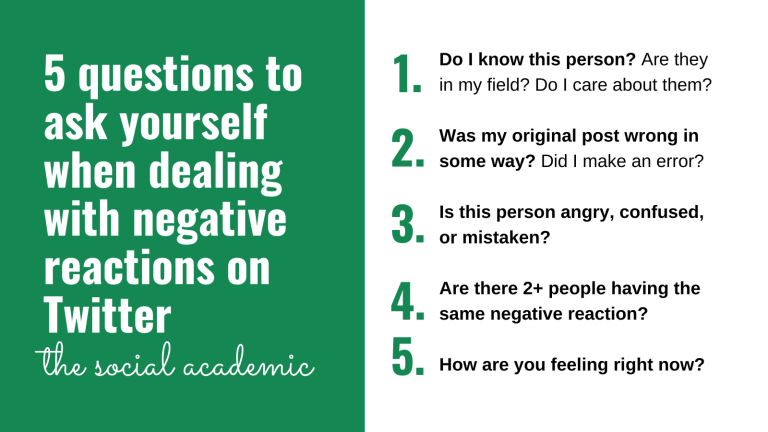

I’ve come up with 5 questions to help you decide if and how to respond.

- Do I know this person/ are they in my field? Do I care about them?

- Was my original post wrong in some way? Did I make an error?

- Is this person angry, confused, or mistaken?

- Are there 2+ people having the same negative reaction?

- How are you feeling right now?

Do I know them? Do I care about them?

The 1st question to ask is if you know them (or know of them, like if they’re in your field). We should take extra care with the people we know personally, or who we’d like to know in the future.

When I say take care, I mean you should take time to

- Read their response

- Consider their feelings/experience

- Respond to them if appropriate

Any reaction from someone you know is one that deserves those 3 things. And while you can start a conversation in response, you can also stick with something easy that requires less of your time.

You could like their tweet to let them know you read it.

Dr. Jennifer Polk (@FromPhDtoLife) says, “If it’s trolls or folks clearly in a bad/weird mood, I tend to ignore. If I get miffed but don’t feel strongly about it, I might just “like” a tweet and decide not to think about it.”

Your response can be a simple reply like, “thanks for sharing your thoughts,” or “let’s talk about this more soon.” Neither of those agree or disagree with what was said. They both acknowledge the time and attention of the person who responded.

You might even decide to ignore it, and not respond at all. Though, I don’t recommend this if someone has asked a question.

Was I wrong?

Were you wrong? Maybe. I’ve made mistakes, typos, errors in tweets before.

Sometimes we’re wrong.

Sometimes we say things out of anger or frustration we later regret.

If you’ve had no public negative reactions so far, deleting your tweet is a good option. Though, be prepared to acknowledge your original tweet, and perhaps your mistake if it comes up.

Remember that deleting your tweet doesn’t guarantee no one has read it or screenshotted it.

You can also add a thread to your tweet where you correct your error. This is the best option if you were wrong + people saw and reacted to it.

You can apologize for your error. You can do that by adding a thread to your tweet, or by retweeting your original tweet with a comment.

If it’s a big error, and lots of people are upset, go ahead and pin your apology tweet to the top of your profile. That way any new people discovering the conversation will find your apology without having to hunt for it.

If people are saying you are wrong, but you are not, the next question is for you.

Are they angry, confused, or mistaken?

Sometimes people are angry, confused about what was said, or just mistaken.

When someone is angry about what you said, you’re better off not responding (unless you’ve made an error). At least, not right away.

You see, they’re still angry right after they send it. Maybe for a couple of hours, or a day. You could try a nonconfrontational response, but that person may just want to argue.

Do you have time for that right now? Maybe, but is that how you want to spend it?

Think about what’s right for you. If you’ve not made an error, I recommend ignoring it for at least a couple hours.

You can respond to people who are confused or mistaken though. That kind of conversation can be nice (and short). They generally don’t turn into arguments.

Dr. Polk says, “If someone says something that’s just wrong, I might correct. It really depends; there’s a lot of nuance here. I would say I’m a lot less combative or interested in defending myself than others. People are allowed to have different takes; I’m allowed to ignore the true haters.”

You are never required to respond or engage with anybody on social media.

That being said, you are not required to educate people on Twitter, though many of you reading are educators at work. If you do not have time/energy to respond, you don’t have to.

However, when someone is a little bit confused or needs a touch of guidance, it’s nice to respond.

Confusion happens. Dr. Polk says, “occasionally there are things I didn’t realize, or folks read a tweet a certain way because of their own positionality and experiences and it’s really not at all what I meant.”

Some of my best supporters on Twitter have discovered me by questioning something I’ve said. When I respond and they know I’ve spent time considering what they’ve said, it can spark a meaningful conversation.

In my experience, you can change minds by pointing someone in the right direction with a single tweet. Don’t Google something for them, but giving them the keywords they’re most likely to find what they need can make all the difference.

Are there 2+ people with the same negative reaction?

When there are multiple negative reactions, you want to pay attention, especially if it’s the same one.

For instance, if 3 people say something like “isn’t that cultural appropriation” you should take a hard look at your tweet to see what you said.

When you get the same negative reaction multiple times, you know people do not like what you said.

Sometimes, that’s OK. Like if you say “Climate change is real. Trust scientists,” you might get a lot of negative reactions. You’re also going to get a lot of positive ones.

Go back to that 1st question, “Do I know them/care about them?” If the answer is no, don’t respond. Spend your time engaging with the people who share positive comments instead.

Those people disagreeing with you might also be trolls. When you poke one, they like to call their friends. Avoid it by not responding. And protect your audience by blocking those who attack. Report anything that’s hate speech or threats.

If on the other hand, let’s say you’ve shared a publication, and multiple people have a negative reaction. This is something a lot of people fear. I’d like to say it doesn’t happen, but I’ve seen these conversations in real time. They might start on Twitter or in a Facebook group, but they don’t stay there.

Here are some of the negative reactions I’ve seen about academic publications on social media

- a major error in methods

- too small a sample size to make such a statement

- plagiarism

- racist

- sexist

- concerns over bias

- did not cite/give credit to minority scholars who published first

- funny typos (this one is more a ‘bad press is good press’ kind of thing)

These are big issues. They might not go viral nationally or make headline news. I’m not going to sugarcoat it for you. Negative reactions to a publication may result in

- petitions

- letters to the editor

- revoked publication

- complaining to your employer

So thinking about those questions is so important.

- Were you wrong?

- Are they angry, confused, or mistaken?

Because these people are in your field. Some you know personally. Others you will meet, or have to work with in the future.

You need to think about what’s right for you. And, if it’s bad, give the editors a heads up, and let them know what might be coming.

I will note, I do not recommend blocking people in this case. You want to know what is being said, and maybe even document it. Blocking in this instance usually leads to

- more work for your friends as they try to keep you updated

- discussion among peers about who was blocked when and for what reason rather than the issue at hand

Responding may diffuse the conversation a bit, but only if you’re nonconfrontational. That might be paired with an apology or correction if that makes sense. Or you might say something like “Thanks for letting me know, I’ll look into this as soon as I’m able.”

Depending on how active the conversation is, I recommend stepping away for some time before you respond. That brings me to the last question.

How are you feeling right now?

How are you feeling is the most important question of the 5. Because if you’re feeling sad or angry, it’s not a good time to respond.

If you’re feeling upset, you’re less likely to

- communicate clearly

- ask questions to figure out why they feel that way/are confused

- avoid an argument

- react with emotion

However you choose to respond, or even if you choose to ignore that reaction, that decision should come from a calm place after you’ve had time to think through all 5 questions.

Some people feel upset for a long time. That might be in response to personal attacks or ongoing harassment. It might be in result to being reported to your employer.

In these cases, many people choose to delete their account or set their account to private. These are valid options.

I spoke with an English professor who tweeted a photo of their kid’s 1st day of school.

This is a great example to share because any other year, this tweet would have gotten only positive responses. But during coronavirus this was not the case. The professor said, “I didn’t think much about the tweet at the time. I never share pictures of my kids’ faces on Twitter because you can’t control who sees it, so it was a picture my wife took from behind us walking hand-in-hand.”

When it’s a personal photo like that, you don’t really expect strangers to see it. Even when you are on Twitter. But this professor decided to use a hashtag, #BackToSchool.

All the sudden, he was getting a lot of likes on his tweet. “I noticed a lot of people liking it and had no clue how they were related to me, then realized it was the hashtag and was a little nervous.”

Then, what appeared to be a young student retweeted with a quote saying the professor would cry when his daughter, her teachers, and classmates died from his decision.

Regardless of your opinions on school reopening, this kind of statement hurts. How do you respond to that, if at all?

This professor deleted his tweet, which I think was a good call because

- the audience that was replying wasn’t one he knew or would interact with in the future

- the reaction received was far greater than the need for the post (there wasn’t a good reason to keep it up)

- this kind of decision is based on so many factors like the family, school, and location (this is too complicated to argue about on Twitter with strangers)

They also set their account to private.

So you definitely want to consider how you’re feeling. And if you need to take time away for now (or forever) from Twitter, that’s okay too.

Back to the 5 questions to ask yourself

Save this infographic

I want you to go through the whole list each time, so bookmark this page. Or, save the infographic image below.

Want to share this graphic on social media? Tag me @HigherEdPR

Subscribe to The Social Academic blog.

The form above subscribes you to new posts published on The Social Academic blog.

Want emails from Jennifer about building your online presence? Subscribe to her email list.

Looking for the podcast? Subscribe on Spotify.

Prefer to watch videos? Subscribe on YouTube.

Tweets in the headlines, when professors make national news

So, what kind of tweets and their negative reactions make the news? Tweets from professors have ended up in publications like

- Inside HigherEd: This professor was forced to resign from his tweets.

- The Chronicle of Higher Education: This 1st person account talks about tweets and academic freedom.

- Times Higher Education: This UK article talks about how US universities are having a hard time firing professors for their tweets.

- New York Times: Tweets can create negative reactions for a long time.

- Washington Post: This professor was fired for “bad humor” tweets.

- Daily Mail: A job appointment was scrapped for this journalism dean after her tweets.

- Yahoo: This professor’s tweet was actually deleted by Twitter.

Some professors have spent a lot of time cultivating fake personas online. Like this white male professor Craig Chapman at University of New Hampshire who pretended to be The Science Femme, a woman of color in science on Twitter. While the account has since been deleted, this archive is a good example of how deleting doesn’t necessarily mean gone.

Over 40,000 people signed a petition for professor Mike Adams’ removal from University of North Carolina Wilmington because of his tweets. Even the university issued a statement about his “Hateful, hurtful language aimed at degrading others,” though they cited free speech. Adams died by suicide not long after.

Students can reach a lot of people on Twitter as well. Don’t respond like this professor since he’s just wrong. One student created a 106-page report of issues with a professor’s tweets.

The tweets these articles are about had a lot of negative reactions. Tweets can end up in national news, for sure. And more ends up in local news, or sometimes your university news or student paper. These white professors pretending to be of color still show up in national news.

I spoke with a faculty-based communications officer at a large public university about professors and tweets gone wrong. She said “my theory is this: ‘live by the sword, die by the sword.’ That is, if you’re going to build a personal brand/online presence by posting strong opinions, criticizing others and saying shocking things that can easily turn against you.”

If you checked out the articles I linked to above, you’ll see each person shared

- a strong opinion

- criticized others

- or said something shocking

Dealing with the backlash can be overwhelming for everyone because the thing is, backlash doesn’t stay on social media. The university communications officer said, “Upset the wrong people and you can set off a tirade of hate emails not just at you and the social media managers, but at your university’s leadership teams as well.”

She recommends that you “build good relationships online like you do in person.”

What I usually say to the faculty and grad students I train is, you tend to know if something is a contentious. You tend to be wary or unsure about that topic. When in doubt,

- wait a day

- ask a friend what they think

- don’t tweet

Subscribe to The Social Academic blog.

The form above subscribes you to new posts published on The Social Academic blog.

Want emails from Jennifer about building your online presence? Subscribe to her email list.

Looking for the podcast? Subscribe on Spotify.

Prefer to watch videos? Subscribe on YouTube.

It’s not that bad (most of the time) when tweets go wrong

Most of the time, negative reactions are stand-alone. One person who didn’t fully understand or who has a different opinion disagrees with you. And that’s okay.

Some of you are saying, what about big accounts though? What if you have a big audience on Twitter? Doesn’t that make it worse?

When I asked Dr. Jennifer L. Polk (@FromPhDtoLife) about how Twitter has been with 48k followers, she said “I think bigger accounts attract more attention (obviously!) but my style is pretty friendly and open, so I don’t tend to get a lot of folks annoyed with me. It does happen. I’ve been a big (in a very small world) account for years now.”

I used to think that the bigger you got, the more trolls you’d run into.

The way I think of it now is if the people who follow you care about you, care about what you share, they’re allies.

I liked chatting with Dr. Walter D. Greason (@WorldProfessor) about this last year, because he talked about how he worked to protect the people who follow him on Twitter. When he blocks someone, it’s to protect his audience of 30k followers on Twitter. To protect the conversations he’s having.

Were you tagged in a conversation on Twitter you don’t want to be part of? In July 2022, Twitter Safety announced the unmention feature would now be available on both mobile and desktop platforms.

Sometimes you want to see yourself out.

— Twitter Safety (@TwitterSafety) July 11, 2022

Take control of your mentions and leave a conversation with Unmentioning, now rolling out to everyone on all devices. pic.twitter.com/Be8BlotElX

Unmention allows you to ‘Leave this Conversation.’ Read more about the unmention feature on Common Thread.

Social media is powerful. Dr. Monica Cox said, “I value authenticity. If something needs to be said, social media provides an opportunity to do it. Being visible and authentic can be problematic for people who don’t want real conversations to happen.” And that sometimes results in negative reactions.

Dr. Cox said we have to remember that “silencing can occur outside social media, so anyone writing on social media should decide if they are willing to face the consequences of sharing their words as themselves on this platform.” This is one reason why some people choose to remain anonymous on Twitter.

The audience you find on social media (or who finds you rather), is following you so that they see what you say.

If you’re dealing with harassers, tell people about it.

If you need help reporting an account, let people know.

If you’re having a freedom of speech issue, ask people for help. Get a petition going. Are you in the USA? Connect with the American Association of University Professors (AAUP).

There is a way to hide when tweets go wrong. Just don’t hide from the people who can help. Sometimes they’ll get into arguments for you before you’ve even seen a negative reaction. And, if you ask for help, they’ll see that too.

I hope this article helps you understand what negative reactions look like. And that you’ve found some options for how to respond.

Subscribe to The Social Academic blog.

The form above subscribes you to new posts published on The Social Academic blog.

Want emails from Jennifer about building your online presence? Subscribe to her email list.

Looking for the podcast? Subscribe on Spotify.

Prefer to watch videos? Subscribe on YouTube.

Virtual. Self-paced. Choose your own adventure.

Free online presence workshop

Jennifer van Alstyne View All →

Jennifer van Alstyne is a Peruvian-American poet and communications consultant. She founded The Academic Designer LLC to help professors build a strong online presence for their research, teaching, and leadership. Jennifer’s goal is to help people feel confident sharing their work with the world.

Jennifer’s personal website

https://jennifervanalstyne

The Academic Designer LLC

https://theacademicdesigner.com