In the excerpt below, Xin Xu and Simon Marginson, in their recent edited volume, Changing Higher Education in East Asia, show how “East Asian higher education is not – and never has been – a unity itself.” By delving into research collaborations, student mobility, and culture and history, Marginson and Xu reveal the diverse and complex tensions at play.

Along with its remarkable development, East Asian higher education is embedded in constant tensions between endogenization, internationalization, and regionalization. Tensions arise both from the East-West relationship and internal dynamics within East Asia. Both ‘the East’ and ‘the West’ are constructed based on a differentiation against the other or the rest – see, for example, Edward Said on the Orient or Stuart Hall on the West. In East Asia, the West is a frequently used reference point, which is more culturally related than geographically specific. The West can include countries and regions sharing occidental cultures, such as Australia and New Zealand, not geographically located in Europe or North America. In response to Bertrand Russell’s book, The Problem of China (1922), Spanish philosopher, José Ortega y Gasset suggested that East and West could fall in love:

Today, the struggle between East and West has the whole demeanour of falling in love. Europe, touched by the deepest spiritual crisis that it has ever suffered, has just discovered Asia sentimentally and is experiencing a phase of enthusiasm. At the same time, the East, especially its most profound manifestation, China, has discovered Europe and fallen in love in equal proportion. The finest Westerners of the present time would like to be a little Chinese, in the same way that astute Chinese would like to be people of London, Berlin, or Paris.

Ortega y Gasset inAn Anthropocosmic View …

However, the East and the West have developed a love-hate relationship. In East Asia, the West is perceived as both a friend and foe. In the continued colonial imaginary, the West is a symbol of modernity and model of democracy. The West is also a potential political and military ally. Incessant internal conflicts within East Asia makes the continuing external presence of Western power welcome in some countries. According to the colonial perception, the East is still inferior to the West and needs to catch up. Such perceptions feed into the continuing white supremacy and Anglo-Euro hegemony in East Asian higher education, where the ‘the foreign moon is fuller’ (a Chinese saying meaning the foreign is always considered better) and where Western knowledge, ideas, models, publications, universities, students, and academics are given more privilege than the local equivalents. At the same time, the West is seen as a conqueror, colonizer, competitor, oppressor, and exploiter who should be cautioned against. This conflicted mindset has deep roots in colonial history – in the Western colonization of Hong Kong SAR, Macau SAR, Vietnam, Singapore, and parts of China since the nineteenth century as well as in Meiji Japan’s ‘leaving Asia to enter Europe’ and the subsequent colonization by Japan of South Korea, Taiwan, Singapore, and parts of China. To uproot the colonial aftermath, East Asian systems push back against the persisting Western influences, some to a larger degree than others. China’s vigilance towards the West is doubled by Cold War memories and recurring ideological conflicts.

The dual perception of the West is never fully resolved in East Asia and its higher education. The modern higher education systems in East Asia bear Western influences, be it the liberal arts paradigm, the Humboldtian model of universities, or the contemporary world-class universities (WCU) templates and rankings that apply indicators rooted in Western reality that not surprisingly reproduce Western dominance. Western influences are particularly evident in both the models and practices of the internationalization of higher education. In this chapter, we use ‘internationalization’ in a neutral normative sense to mean interactions, cooperation, mobilization, and communications between nations (international); but internationalization practice must always be interrogated in terms of the models, norms, and behaviours it fosters.

Internationalization approaches differ across the East Asian systems. Here, geography and contextualized cultures matter. Island states can be restricted by their limited resources and face potential dangers of isolation from the continental world. Island systems like Japan, Singapore, Taiwan, Hong Kong SAR, Macau SAR, and South Korea (a peninsular state separated by North Korea from the continent) are actively outward-looking, keen to develop external links and maintain a strong presence in the world, to be a nexus of mobilities and to avoid insular status. In comparison, as quasi-continental states, China and Vietnam have resources within the nation, tensions with bordering nations and a more open choice about external engagement. Such states oscillate between times of extensive internationality and times of self-sufficiency and even isolation as the histories of the United States and Russia show. Mongolia is a landlocked country between China and Russia, mostly restricted in resources, vision, and engagement with the outside. While the world is connected via the Internet, geographically shaped mindsets persist in the system orientations to internationalization.

Internationalization easily becomes a synonym of Westernization.

Western supremacy could entrench internationalization approaches: national WCU schemes which follow Western models, international partnerships and branch campus mostly developed with Western universities, asymmetrical mobility of students and academics, asymmetrical cross-border research collaborations, the reform of teaching and curriculum to incorporate Anglo-American elements like English-medium instruction, and promotion of Anglo-American elements in research such as prioritizing English-language publications. Although East Asian systems are rising in global science in the bibliometric sense, as outlined below, the epistemologies, discourses, methodologies, and evaluative criteria bear Western imprints. Internationalization easily becomes a synonym of Westernization.

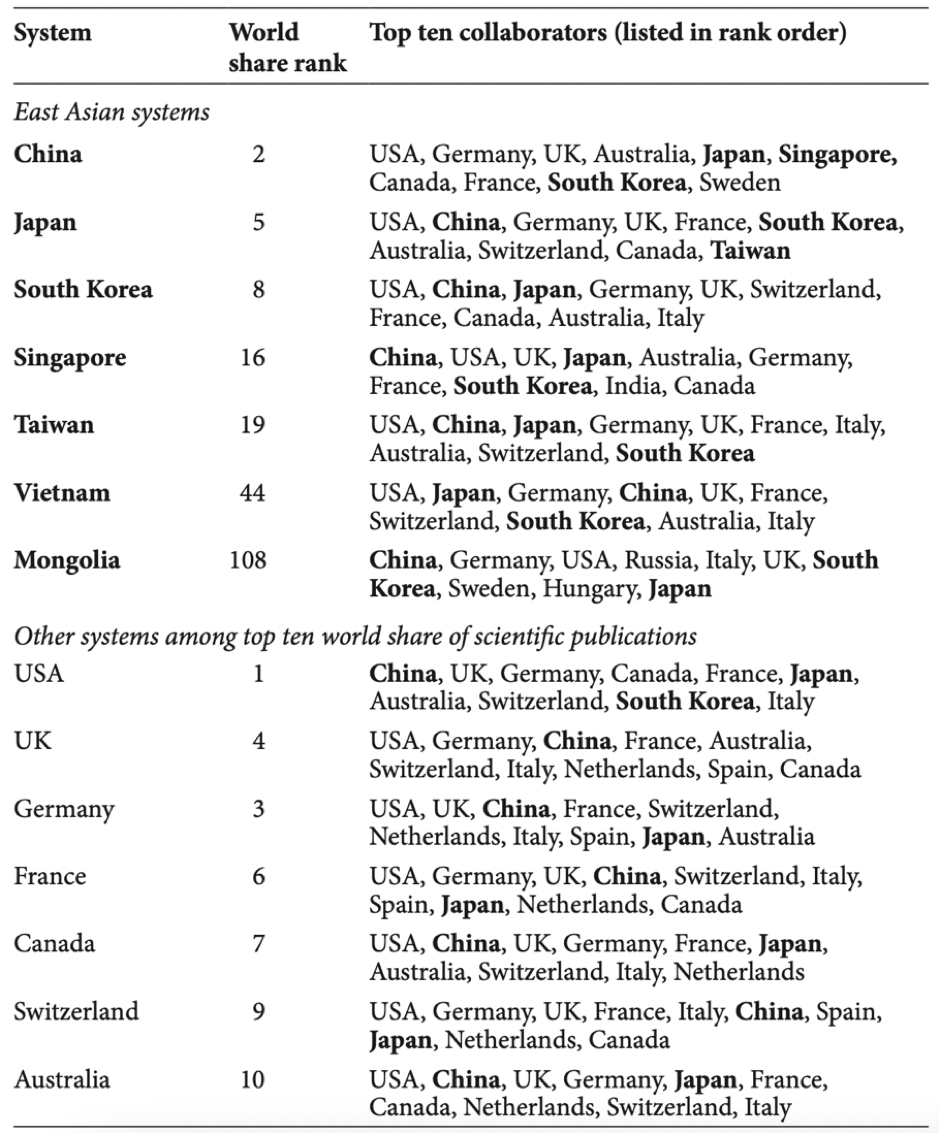

Note: East Asian systems in bold; no data for Hong Kong and Macau SARs.

Source: Authors, original data from Nature Index (2021)

Despite an immense local knowledge pool, countries and regions in East Asia prioritize publications in internationally recognized journals, mostly Anglophone and Western. Table 1.5 illustrates strong but unbalanced research collaboration ties between East Asia and the West. Academics in almost all East Asian systems work most closely with researchers from the United States, though Singapore and Mongolia are exceptions. In East Asian systems, the top five collaborators always include China and Japan, but the rest are all Western; and while other East Asian systems appear in the top 10 collaborators, Western systems have much stronger presence, despite the total weight of East Asian papers in science output. Obversely, in Western countries that rank high in the volume of science publications, only China from East Asia figures in the top five collaborators; all the rest are Western countries, except in Australia where Japan is fifth collaborator. Furthermore, not all collaborations are conducted on an equal basis. Some retain colonial and exploitive features.

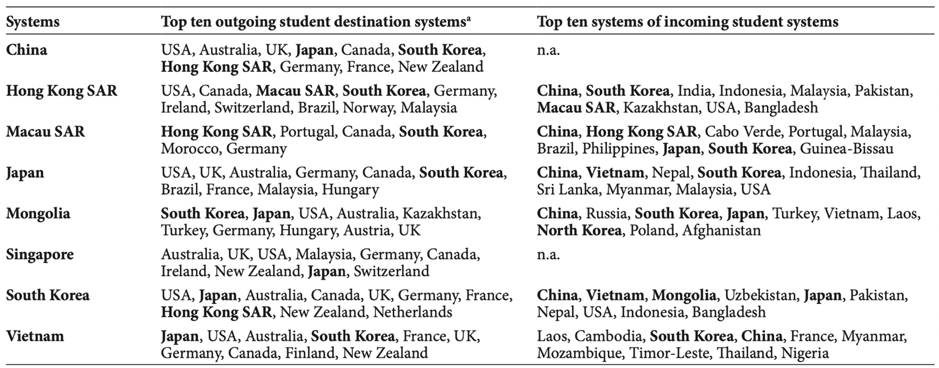

Note: n.a. indicates data not available.

Data not available for Taiwan: for China and Singapore’s inbound students’ origins; for Macau SAR’s destination country after Germany; East Asian systems are in bold.

Source: Authors, original data from UNESCO (2021)

Patterns in international student mobility between the East and the West are more asymmetrical than the relations in research. As Table 1.6 shows, while Western countries are the top destinations for students moving out of most East Asian systems, Western students do not dominate the lists of students moving to East Asian countries. East Asian countries mostly attract students from East Asia, Southeast Asia, and Central Asia – another example of bottom-up regionalization. Only Hong Kong SAR, Macau SAR, Japan, South Korea, and Vietnam attract Western students from the United States, France, and Portugal (note that in each case there is a historical imperial or neo-imperial relationship). This indicates persisting perceptions of the Western countries as old acquaintances through coloniality, as bearers of modern knowledge and cutting-edge research, as providers of quality education and valued accreditation, and as guarantors of better life and employment opportunities. The ‘Western Dream’ (especially the American Dream) is still alive and well. But the landscape is changing, with Singapore, Hong Kong SAR, and then China rising as regional educational hubs, offering familiar cultural magnets and rising prospects for better futures.

But the landscape is changing, with Singapore, Hong Kong SAR, and then China rising as regional educational hubs …

East Asia is never fully Westernized. The fundamental cultural differences between the East and the West make it impossible to fully assimilate each other. East Asian higher education systems are resilient and are increasingly active in shaping their own agendas, working with not only global benchmarks, but also national-cultural models. There are pushbacks from academics, institutions, and governments against the reproduction of Western supremacy in national higher education systems. National policies issued in 2020 by the Chinese government firmly asserted the importance of domestic publications in the Chinese language and rejected the previous ‘(S)SCI supremacy.’ The constant emphasis on ‘Chinese characteristics’ and ‘Chinalization’ of higher education and research again indicates endogenization efforts. De-Westernization also happens in scholarly investigation on (East) Asia. The inter-referencing approach proposed by Chen Kuan-Hsing (2010) in the book, Asia as Method, raised a possibility of comparing Asia with Asian characteristics, not against Western standards. Similarly, Japanese Sinologist, Yoshimi Takeuchi, expresses the idea of replacing the East-West dichotomy with a broader framework:

It is important in analysing Japan to refer to the United States and Western Europe, for they represent the advanced nations of modernisation. Nevertheless, we must also look elsewhere. In studying China, for example, we should not limit ourselves to seeing this nation only vis- à -vis the West. It was at this time that I realized the importance of conceiving of modernisation on the basis of a more complex framework than that of simple binary oppositions.

Takeuchi, What Is Modernity: Writings of Takeuchi Yoshimi, pp.156–7

_______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

This post is opinion-based and does not reflect the views of the London School of Economics and Political Science or any of its constituent departments and divisions.

_________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Note: This excerpt from Chapter 1, “‘The Ensemble of Diverse Music’: Internationalization Strategies and Endogenous Agendas” (pp. 21-27) has been reproduced with kind permission from the editors, Xin Xu and Simon Marginson, who are also the authors of this chapter, and the publisher, Bloomsbury. This title, Changing Higher Education in East Asia, was published in 2022 and is part of the Bloomsbury Higher Education Research series.

Image: capclubstudio on PxHere