Tom Priestley, who has died aged 91, knew early on that he wanted a career in the arts. “But my father had covered so much territory, there wasn’t much left,” he said. He was the sixth child and only son of the playwright and novelist JB Priestley.

The discipline he eventually chose, and excelled at, was film editing. He won a Bafta for Morgan: A Suitable Case for Treatment (1966), Karel Reisz’s dark comedy about conformity and rebellion, starring David Warner and Vanessa Redgrave. He was also nominated for an Oscar for John Boorman’s thriller Deliverance (1972), with Burt Reynolds and Jon Voight. It was adapted by James Dickey from his own novel about four friends who are terrorised by Appalachian locals while on a canoeing trip.

Boorman recalled showing a rough cut of the film to executives at Warner Bros: “The response was one that I got used to, which is that people just walked out without saying a word. People were sort of devastated by it.”

Priestley finessed the film’s air of tension and discomfort, not least in three unforgettable scenes that loom large in the history of suspense cinema: the tense “duelling banjos” encounter, the harrowing ambush during which one of the men is raped at knife-point, and the shock ending, which gives both movie and audience an electrifying jolt after the action has seemingly concluded.

He was also alert to moments of spontaneity. “A lot of the river stuff was in effect improvised because they were actually doing it,” he pointed out. “Let’s say the canoe going down a rapid might unexpectedly twist round or somebody’s hat would fall off – we incorporated that into the final cut.”

Priestley edited Boorman’s previous film, Leo the Last (1970), a class satire set in west London and starring Marcello Mastroianni. He worked again with the director on the ill-starred horror sequel Exorcist II: The Heretic (1977) after the original editor resigned.

His other films include Peter Brook’s Marat/Sade (1967), The Great Gatsby (1974) starring Robert Redford and Mia Farrow, The Return of the Pink Panther (1975), Roman Polanski’s Thomas Hardy adaptation, Tess (1979), and the teen-punk drama Times Square (1980).

For the director Michael Radford, Priestley edited Another Time, Another Place (1983), a wartime love story set in Scotland; an adaptation of George Orwell’s 1984, released in that year and featuring Richard Burton’s final film performance; and White Mischief (1987), inspired by a real-life murder case among the British upper-class in colonial Kenya.

Priestley’s philosophy of editing prized “the continuity of emotion” over the more conventional kind.

He was born in London and spent his early years there in a house previously occupied by Coleridge, and at a home in the Isle of Wight. His mother, Mary (nee Holland), known as Jane, was previously married to the humorist DB Wyndham Lewis. She was a keen ornithologist who later co-authored several books on birds with her third husband, David A Bannerman. The Peter Pan author JM Barrie was Tom’s godfather. His first encounter with one of his father’s plays came when he was taken as a baby to rehearsals of Dangerous Corner.

He described his early childhood as “a traditional upper middle-class nursery life … There was a nanny who looked after me and my younger sister. We were a separate group. If there were no guests, then we were allowed down for Sunday lunch.”

At the age of eight, he was sent to Hawtreys, a Kent boarding school, where he was permitted to listen to his father’s wartime broadcasts, Postscripts, on the radio. Growing up, he was accustomed both to his father’s frequent physical absences (he never visited him at school) and a certain emotional remoteness when they were together. “To be perfectly honest, he liked women,” he said. “I suspect they were more important to him than I was.”

He went to Bryanston school in Dorset, then completed his national service with the Royal Engineers. He read classics and English at Cambridge, where he ran a play-reading club attended by EM Forster. After graduating, he spent a year teaching English in Athens.

Returning to London, he got a job as an assistant film librarian at Ealing Studios, and moved into sound work. His first credit was as assistant sound editor on Dunkirk (1958). He was also sound editor on Polanski’s claustrophobic horror Repulsion (1965), though by this time he had moved into film editing.

He was an assistant editor on Bryan Forbes’s Whistle Down the Wind (1961), about three children who mistake an escaped convict (Alan Bates) for Jesus, and Lindsay Anderson’s This Sporting Life (1963), starring Richard Harris as a brutish rugby player. He was the supervising editor on two surreal and highly original state-of-the-nation dramas: Anderson’s O Lucky Man! (1973), with Malcolm McDowell as a coffee salesman travelling through an increasingly bizarre and hostile Britain, and Derek Jarman’s punk gem Jubilee (1978), featuring a time-travelling Elizabeth I.

In the early 1990s, Priestley quit editing, having “reached the point when I felt I had achieved all I could … I was only using part of myself, and life seemed to consist of the flickering images I saw in the lens of my editing machine. Instinct told me I needed to get out more into the world and reach out to people.”

This he did by teaching at the National Film and Television School, and by promoting his father’s life and work. He had already made a documentary about him, Time and the Priestleys, which was intended as a 90th birthday tribute but became an obituary instead when his father died shortly before broadcast in 1984, at the age of 89. He administered his father’s estate for the rest of his own life, helping to organise events around his centenary in 1994, as well as becoming president of the JB Priestley Society.

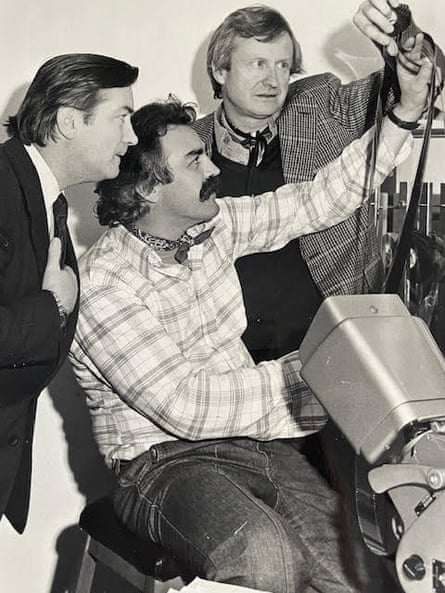

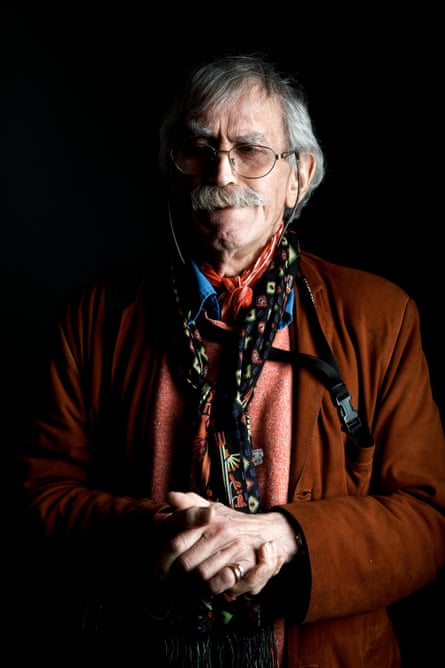

Tom was a stylish dresser, even a dandy. To celebrate his Oscar nomination in 1973, the Evening Standard ran a double-page spread on his wardrobe. “He’s confident of his own style, rarely self-conscious, liberated even,” the paper reported, praising the Moroccan kaftan he wore “instead of a dressing gown” and the “hooded Arab cape … when eating out locally” as well as his “winter moustache” and “Byronic” hair.

His appearance was a minor source of friction with his father. “It would be going too far to say he was jealous of me,” he told the Oldie in 2016, “but he was deeply offended by my jeans.” He was also “disappointed” to discover Tom was gay, and found it “difficult to adjust to”. Tom’s response: “Well, so did I.”

He is survived by 16 nieces and nephews.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion